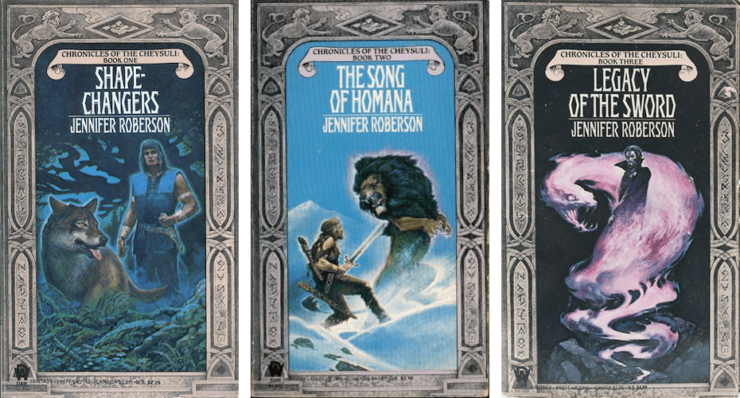

When I started lining up readings for this chapter on Shapeshifters Who Are Not Werewolves, the first book series I thought of was Jennifer Roberson’s chronicles of the Cheysuli. It began with Shapechangers in 1984 and ended in 1992 with the eighth volume, A Tapestry of Lions. It’s a classic of its genre, and I welcomed the chance to reread it.

When I first read these books, when they were new, I read them for the pleasure of living in a new fantasy world. Now that we’re both a fair bit older, I’m delighted to report that the books hold up. There are things about them that are of their time, as we’ve been known to say, but I don’t have to talk about that here in the Bestiary. I get to focus on the best part: the shapechangers.

The world they live in is a traditional fantasy world, with horses and swords and castles and kings. The central kingdom of the series, Homana, was founded by the dark-skinned, black-haired, Native American-like Cheysuli, but colonized by the tall, blond, often blue-eyed Homanans. Cheysuli are magical people. Homanans are ordinary humans. The Cheysuli, for Reasons, allowed the Homanans to rule, and swore themselves in service to Homanan kings—until one of those kings attempted to perpetrate genocide on the Cheysuli.

Shaine has managed, in less than a generation, to turn his people completely against the shapechangers. They’ve been hunted almost to extinction, and they’re profoundly and unremittingly hated for what they are.

Alix, the protagonist of Shapechangers, believes herself to be a simple crofter’s daughter. She’s head over heels for Shane’s handsome heir, his nephew Carillon—and Carillon is head over heels for her. But he can’t marry her. He has to marry a princess. He presses her to become his mistress, which is a more or less honorable position in Homana.

Alix is stubborn. Very, very stubborn. Did I mention that she’s stubborn?

One fine day, Alix and Carillon are both abducted by a demon from the woods, a Cheysuli named Finn. Cheysuli numbers are so low that their men are kidnapping Homanan women and forcing them to bear Cheysuli offspring.

Did I mention that Alix is stubborn? She can’t escape him, but she does resist him.

And then she learns who and what she really is, and the real reason why Shaine wants to wipe the Cheysuli from the earth. It’s not that they’re demons or that they can turn into birds or animals. It’s that Shaine’s daughter fell in love with Shaine’s Cheysuli liege man and ran away with him, and had a daughter by him. That daughter was to be left out in the woods to die (or be found by her Cheysuli relatives), but Shaine’s military commander took her in, left his post and became a simple crofter, and raised her in ignorance of her identity.

To add to the irony of it all, Alix is in fact Finn’s half-sister. Finn’s clan leader, his adopted brother Duncan, who is no actual relation to Alix, makes it clear that Alix is his fated bride. She may want Carillon, but fate says she’ll never have him.

Fate is a powerful force in the world of the Cheysuli. Everything they are and do is based on Tahlmorra—destiny, fate, the preordained will of their gods. A person may try to resist that fate, but it never ends well.

The driving force behind the Cheysuli is an ancient prophecy that every one of them is bound to fulfill. According that prophecy, a Cheysuli will rule Homana again, but that is just a step in a process that will end with a king descended from every race in their world. It’s a grand divine plan and a dedicated breeding program, and Alix and Duncan are key parts of that. So, as he eventually discovers, is Carillon.

The political machinations are complicated and often fraught, and they have a tendency to drown out the real heart of the books, which is the nature and magic of the Cheysuli. Roberson is at her best when she writes of that. Her prose soars and sings.

It takes about a volume and a half for the series to find its feet. Alix is in the running for World’s Most Annoying Protagonist; her book is a fine fast adventure with some intriguing ideas and characters, but it’s the second volume, The Song of Homana, told from Carillon’s point of view, that really makes clear what the Cheysuli are and where their powers come from.

In Alix’s time, only Cheysuli men are able to shapechange. Their powers come from a magical animal companion, the lir, with whom they can communicate telepathically, and through whom they’re able to take the shape of whatever animal or bird the lir happens to be. Without a lir, a Cheysuli cannot shapechange. If the lir dies, the Cheysuli becomes an empty shell, a shadow of a man. He goes off into the woods and seeks his death.

Alix is able to communicate with all the lir. She doesn’t need one in order to shapechange: she can turn into whatever animal form she can clearly imagine. She’s a throwback to the original Cheysuli, and she’s a harbinger of what’s to come.

Carillon is part of this prophecy as well, and fate drives him inexorably toward the throne of Homana. When he’s about to become king, Finn takes him into a hidden part of his own palace, and subjects him to an ancient ritual in which he is able, for a short time, to understand what it’s like to be Cheysuli. This is where Roberson’s writing really takes off; parts of it gave me chills as I reread it.

Buy the Book

One for My Enemy

These shapechangers regard their ability as a gift of the gods. Ordinary humans hate and fear them, but they’re proud of what they are. They’re the gods’ own children, with three great powers: shapechanging, healing, and mind control. They’re also warriors of unmatched skill and prowess, able to fight in both human and animal form, with the doubled threat of their lir. They’re a formidable fighting force.

Their opposites and their fated enemies are the Ihlini, sorcerers in thrall to the dark gods. Ihlini can transform unliving things into twisted travesties of animals; they can do the opposite of healing, can take away life and health from a person; and they can prevent Cheysuli from shapechanging, and keep them from communicating with their lir. The lir cannot fight the Ihlini, because the gods forbid it.

It’s a great example of magic-with-a-price. The lir is deeply bonded, wise and powerful, but it’s also a deep vulnerability. If an enemy wants to destroy a Cheysuli, he’ll kill the lir. Even wounding one can do serious psychological damage.

One thing I really enjoyed about the reread was seeing the resonances of Roberson’s predecessors. She has a real gift for building on the authors who came before, while making the ideas entirely her own.

Alix’s ability to communicate with all the lir recalls Anne McCaffrey’s Lessa, who can hear all the dragons—and Lessa is much the same kind of person, too, headstrong, stubborn, and often selfish. I caught echoes of the Weres of Andre Norton’s Witch world, especially Year of the Unicorn, in which a caravan of unwilling brides is shipped off to the mysterious and much feared Werefolk as part of a military alliance. The strict determinism of Cheysuli culture, the absolute power of fate and prophecy, recalls Norton as well, along with a fair few other fantasies of the same period. Susan Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising, for example.

Roberson does her own thing with all of it, and she does it well. Her shapeshifters are proud of what they are. Some like Alix who grew up outside of the clans, who were indoctrinated with human prejudice, may start off fighting their destiny, and may pay a terrible price for it. But the power itself, the ability to change, is a blessing and a gift, and not a curse.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks. She’s written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.